Conservation paleobiology and local ecological knowledge of subalpine plant communities in Acadia National Park

The granite ridges of Acadia host unique, isolated communities of sub-alpine plants, including species at the southern edge of their ranges, such as black crowberry and alpine blueberry. As temperatures continue to warm, these habitats above treeline and the plants and animals they support are at risk of disappearing. Many of the plants are believed to be relicts of the tundra that once covered the mountains at the end of the last Ice Age, but the details of this history, and how subalpine plants respond to climate changes at a local scale, are not well understood.

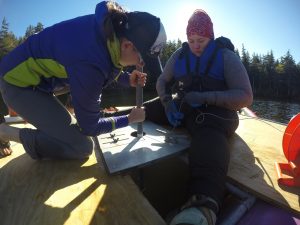

Caitlin McDonough MacKenzie researches the ecological stability of plant communities, reconstructing vegetation changes through time by studying the layers of plant pollen and fossils in the sediment of high-elevation lakes. In her current research as a David H. Smith Conservation Research Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Maine, McDonough MacKenzie collected a sediment core from Sargent Mountain Pond, which previous UMaine research showed to be the first lake to emerge in Maine after the most recent glacier receded. Previous work at Sargent Mountain Pond had focused on nutrient cycling, and pollen analyses were limited in temporal range and resolution. McDonough MacKenzie’s new core incorporates both pollen and fossil data from the entire Holocene (~14,000 years) at a fine-enough resolution to capture vegetation responses to rapid warming events in the past.

This Second Century Stewardship project will add data from a new sediment core from the Featherbed, a remote pond on the west slope of Cadillac Mountain. With data from wind speed and direction sensors installed at both ponds, she will be able to map the source populations of past and current pollen that drift into the lake as dust and rain. “This will improve our understanding of the paleobiology data, and also help us predict the source populations for plants that may migrate up the mountains,” she said.

McDonough MacKenzie is not just interested in data she can measure, but recognizes that humans also hold knowledge in layers of memory. The Wabanaki people have known the mountains and lakes of Acadia for millennia, and their histories and practices may reflect experience of environmental change as well as valued mountain plants. McDonough MacKenzie hopes to listen to, learn from, and highlight Indigenous perspectives of place, to improve climate change vulnerability assessments and illuminate the full history of subalpine vegetation in Acadia.